It’s been some time since I last wrote - I decided to take a few weeks off over the Christmas holidays but inadvertently broke my writing habit. Lesson learnt for next time.

This week I wanted to look into oracles and DONs (Decentralised Oracle Networks).

Farming and insurance

If you’re a farmer and want to insure your farm against poor rainfall, you’d normally take our a policy with an insurance provider. If there isn’t sufficient rainfall in a particular year you’d submit a claim. The insurance provider will use its data sources (usually bought from a third party such as AccuWeather) to determine whether your claim is valid based on the level of rainfall. After a long process you’re likely to get some compensation if the data backs your case.

How does this work in the Web3 world? You take out an insurance policy in the form of a smart contract, which pays compensation based on pre-agreed level of rainfall. A smart contract works in the same way as the traditional insurance example above: you’re compensated if there isn’t sufficient rainfall. The only difference is that there isn’t an insurance company per se: it’s just some code stored on the blockchain.

Oracles

Oracles are intermediaries between blockchains and the outside world. Traditionally, an oracle is a portal through which the gods speak to people. The idea in technology is exactly the same - oracles are bridges between two worlds (i.e. blockchains and the outside world).

Why are they useful?

Blockchains have few uses if they can’t interact with data from the outside world. Why not simply connect a data source? e.g. if you’re looking for the amount of rainfall in a certain area, can’t you just feed an AccuWeather data source?

There are a couple of reasons why this isn’t possible:

- The data source is likely to change, so all the nodes in the blockchain network won’t agree on the data. This is more pronounced when looking at exchange rates, which change at a very high frequency.

- Reliance on a single data source is dangerous since there’s no redundancy, and it can easily be manipulated. A key design feature of blockchains is immutability, so mistakes are irreversible.

Oracles solve the first problem by inputting data onto the blockchain in the form of a transaction. This way if all the nodes of the network agree on the transaction, by definition they’ll agree on its data.

To solve #2, you need some more decentralisation:

Decentralised Oracle Networks (DONs)

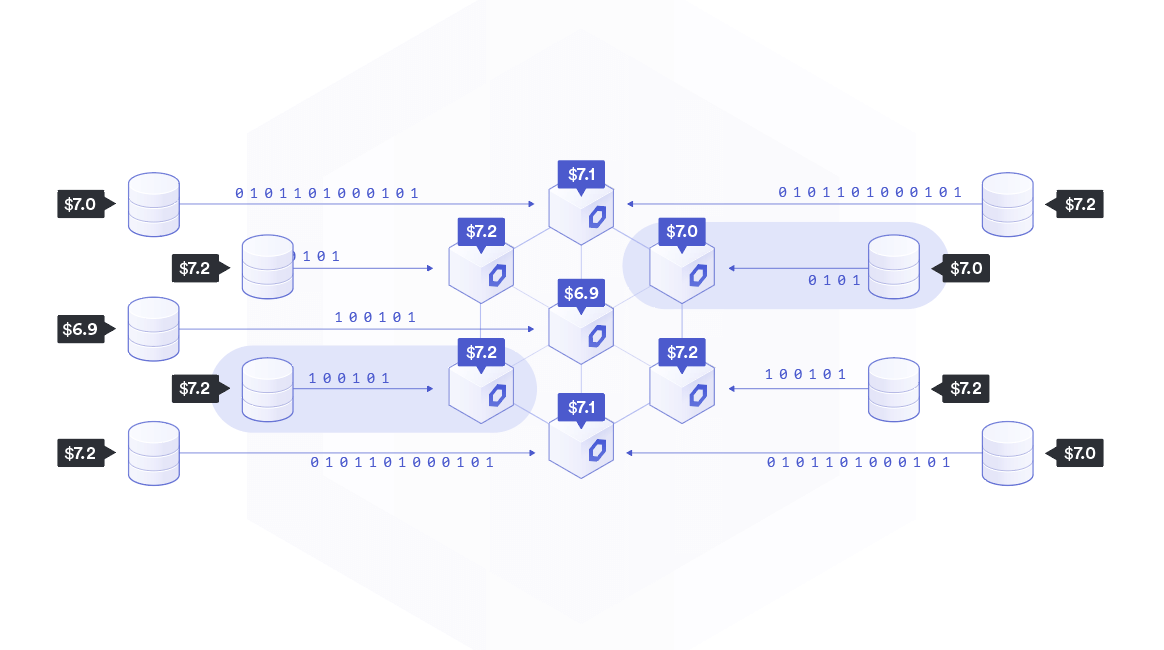

Oracles suffer from the same problem as any centralised data source. If an oracle is manipulated or is offline for some reason, smart contracts won’t work as intended. The solution is to use a DON, which is a network of oracles, each with independent data feeds (e.g. multiple weather feeds from providers such as AccuWeather, Meteomatics).

From Chainlink:

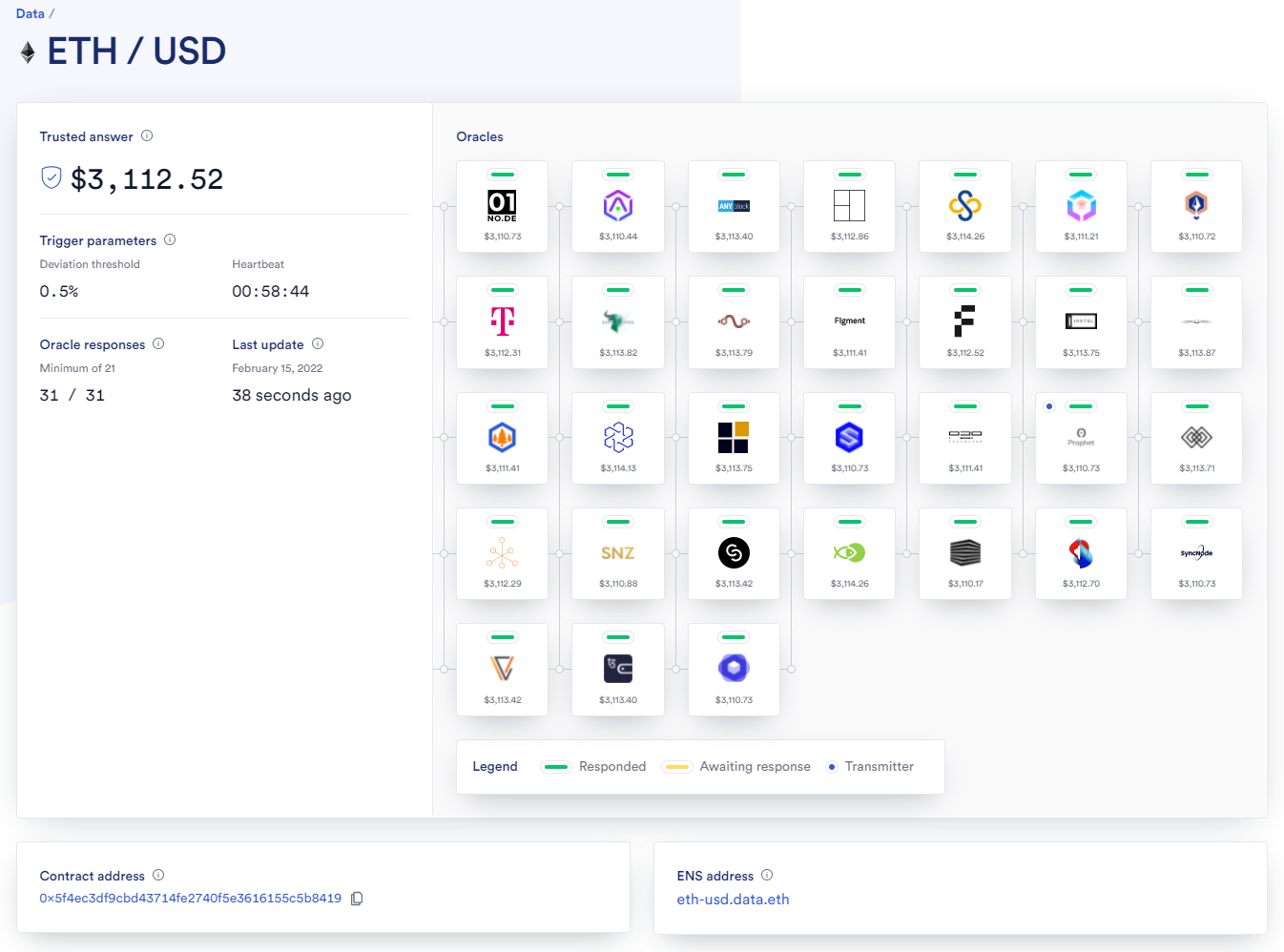

A decentralized oracle network is a group of independent blockchain oracles that provide data to a blockchain. Every independent node or oracle in the decentralized oracle network independently retrieves data from an off-chain source and brings it on-chain. The data is then aggregated so the system can come to a deterministic value of truth for that data point.

The glaring problem

Web3 is all about decentralisation. Some fields lend themselves better to decentralisation (e.g. exchange rates, which are actually highly aggregated before being fed into oracles). In this case aggregated data is taken from multiple (decentralised) sources and a final value is then decided by the DON.

For many other domains, although there are multiple, trusted data sources feeding the DON, most of these ultimately lie in the hands of centralised, private corporations. Perhaps there isn’t a way around this in the short term, but we’d expect to see more decentralised data sources in the future.