Languages are hard to learn. You can use some of the tricks outlined in the previous post, but there’s no magic bullet when it comes to learning them - they’re ‘irrational, irregular, and uneconomical’1. For example, in English we say three dogs. There’s no need for dogs to have an ‘s’ at the end. Plurality is already implied by three, so the ‘s’ redundant.

To make languages easy to learn and speak, linguists have invented auxiliary languages - i.e. languages where the grammar and vocabulary are completely2 made up. These auxiliary languages remove some of the irrationality and irregularity that have crept into natural languages over the years. They also have a humanitarian mission - a language through which all citizens of the world can communicate. The hope is that a common understanding will reduce conflict and warmongering.

Esperanto

Esperanto is the most successful auxiliary language, and it’s the only one that has native speakers (i.e. people born into Esperanto households). It was conceived in 1887 by L.L. Zamenhof, a Polish ophthalmologist, to ‘reduce the time and labour it takes to learn foreign languages, as well as to act as the world’s second language.’ Proponents say you can learn it in just a matter of months3. Its grammar is very regular - you can make new words by adding prefixes and suffixes onto a root4. Here are some examples5.

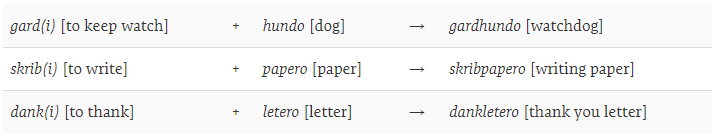

You can use these to make compound words

This allows someone learning to make up new words, based on words they already know. Its vocabulary is primarily Latin (about 75%), with the remainder from Greek, English, and German.

Esperanto wasn’t the first auxiliary language, nor the last. The most recent one, Globasa, is only a couple of years old. Other significant auxiliary languages include Volapuk, Ido, Novia, and Interlingua.

What’s lost?

Whilst I agree with the diagnosis that languages are irregular, irrational, and uneconomical, I’m not a pro-auxiliary language. Here’s why: language shapes our thought. The early auxiliary languages were made using vocabulary from European languages, and even though more recent ones sample vocabulary from a wider range of languages, they naturally don’t capture all the concepts important in each language.

Conflicts stem from deep-rooted misunderstandings, and they’re often based on cultural and linguistic nuances. I’m uneasy about the humanitarian mission: when one group of people doesn’t understand why a certain thing is so important for another group, it’s usually because they don’t have the vocabulary in their own language to conceptualise the issue.

Modernity’s press for standardisation of language loses depth, intricacy, and meaning for so many people. I think they won’t be part of the solution leading to world peace. Having said that, learning an auxiliary language can be a good use of time - you can learn a lot about how languages work and foster strong communities based on these shared interests.

Sign up to my blog here

- Frederick Bodmer, The Loom of Language

- Actually, they’re usually borrowed from other languages

- It’s even on Duolingo

- Other natural languages work in a similar way. Arabic is an example I’m familiar with

- By Daniel Adler