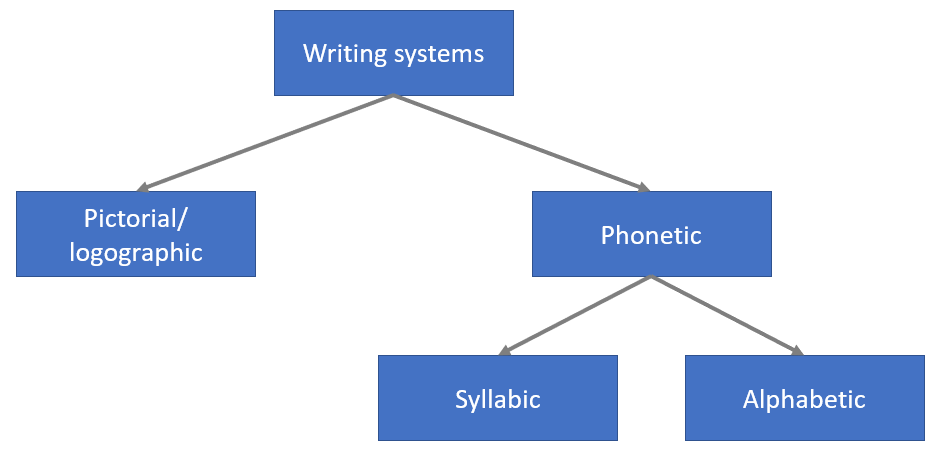

Ever wondered why alphabets are so similar? Evidence suggests the alphabet was only invented once so all alphabets can be traced to a single source. To understand its history, we also have to understand other types of writing systems. Alphabets are just one type - many other writing systems exist and are still used by living languages.

For example, Chinese languages use a logographic system and Japanese uses a syllabic system (based on logograms). Before getting to alphabetic systems, it’s worth going through these other types.

Pictorial systems

Pictograms

This is the simplest form of picture writing, where pictures represent words or concepts. The meaning of a pictogram is immediately evident. For example, the sun would be represented by a circle. Linguists argue that pictograms can only express part of what can be communicated by a language (compare that with English, where everything in the language can be articulated in writing).

Logograms

These are similar to pictograms, but the pictures have lost their literal meaning (e.g. a circle might mean unity). People who understand different branches of a logographic language (e.g. Chinese languages) may pronounce a logogram completely differently. They can only communicate through writing, and not orally since they pronounce logograms differently. An example we’re all familiar with is numbers: both a Frenchman and an Englishman understand what’s meant by the symbol ‘4’, even though one pronounces it ‘quatre’ and the other ‘four’.

Phonetic systems

Phonetic systems are where symbols represent a sound of the language.

Syllabic

A syllabary is a set of symbols that represent syllables, which make up words. Japanese is a syllabic language: words are made of open monosyllables, e.g. YO-KO-HA-MA. This works for Japanese because the number of possible syllables is limited by the number of consonant and vowel combinations. Such a system wouldn’t suit English. Each of these words would need a separate symbol: ‘bag’, ‘beg’, ‘big’, ‘bog’, ‘bug’, ‘bad’, ‘bed’, ‘bid’, ‘bod’, ‘bud’, ‘bead’, ‘bide’, ‘bode’, etc. If a syllabary were used for English we’d need 10,000 separate symbols to account for the different syllables.

The coming of the alphabet

Modern alphabets are all derived from the same source (see ABCD Family Tree diagram below). We can trace the transformation of around 22 Egyptian logograms into the Phoenician alphabet around 1000BCE - 1500BCE. This early alphabet only had consonants so wasn’t an alphabet in the strict sense1.

An alphabet with only consonants worked because Semitic languages are made up of words that have three consonants. ‘Vowels’ are pronounced in between these consonants but aren’t written down - e.g. the Arabic word for milk, laban, is written with three letters in the Arabic script (لبن).

Interesting side note: Arabs who are learning English will often write words without any vowels at all. Something like this: vwls, intrstng, chldrn

Greek additions

Greek is a language rich in vowels. To adapt the Phoenician alphabet to their own use, the Greeks had to introduce vowels. They did this by taking Phoenician letters that they had no use for (ālep, ayin) and turned them into vowels, as well as creating additional letters for other vowels. The word ‘alphabet’ actually comes from the first two letters of the Greek alphabet - alpha and beta.

This then evolved into the Latin alphabet (through the Etruscan one) that I’m using to write this post. This infographic from Ryan Starkey nicely shows the evolution of different scripts from Egyptian logograms.

The role of scribes

There are many variations of letters amongst different languages, even within the Latin alphabet. Why do some alphabets include additional letters e.g. ø, ü? Scribes introduced them when they came across a sound that doesn’t fit the range of letters they had. Scribes may also create random combinations of existing symbols to represent other sounds - e.g. TH, or SH.

English has Latin, Greek, and Teutonic origins. By paying attention to the letters a word contains, you can tell its origin and guess its meaning: if the word contains SH (so spelt) it’s of Teutonic origin, but if it contains the SH sound spelt as TI (e.g. nation) then it’s of French-Latin origin. Another example is GH (when silent in English, e.g. in light) - these words have Teutonic origins2, and when you come across a German word you can guess its meaning. E.g. German for light is licht, night is nacht, right is racht. Note the change in sound from a silent GH to a ‘k’. More about these patterns in the coming posts - this was just a taster.

Sign up to my blog here

- In this post, I haven’t differentiated between true alphabets, abjads, and abugidas. True alphabets contain both consonants and vowels. Abjads only have consonants. Abugidas also only have consonants but the shape of the letters changes slightly based on the vowel used.