In a previous post we saw that virtual money came before physical money. Since then the world has gone through periods dominated by either virtual money or physical money. We think we’re entering into a virtual money cycle with rise of cryptocurrencies, but this actually happened when nations abandoned the gold standard. Money is no longer tied to anything physical.

After writing the posts on debt and the origin of money, I wondered how money is created, and I found the answer in a paper by the Bank of England.

The different types of money

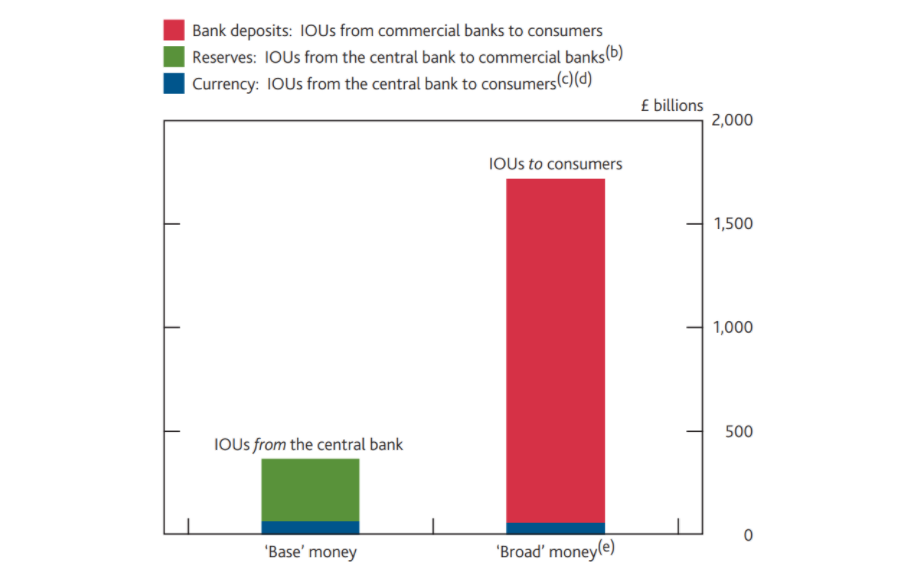

Money is circulating debt - it’s a string of IOUs. To understand how money is created it’s worth knowing the three types of money that exists in the financial system.

-

Currency - these are banknotes and coins issued by the central bank. In the UK, it hasn’t been convertible to gold (or any other asset) since 1931. These make up a very small proportion of the total money in an economy

-

Bank deposits - this is money held in current or savings accounts. Bank deposits are the default form of money in the modern age, and are digital.

-

Central bank reserves - this is money banks place with the central bank. Reserves banks to settle transactions with other banks. Central bank reserves can be swapped for currency at any time if there is a need (all the central bank has to do is print them)

This chart shows the proportion of each of these types of money in circulation. Bank deposits make up 97% of the total money in circulation.

How is money created?

Historically the central bank would print notes and mint coins that would ultimately end up with consumers. Although this is somewhat true in the modern economy, it only accounts for a small amount of money in circulation (blue bar in the chart). The real question is what are bank deposits and how are they created?

The simple answer is that banks just create money. From nothing.

The common understanding is that loans are created by banks lending depositors’ money. Since the bank understands that everyone will not need all of their money at once, they lend the amount they’re confident won’t be withdrawn in the short term.

The reality is slightly different: deposits (i.e. savings) don’t increase the amount of funds available for banks to lend out. Instead, deposits are created by banks making loans.

For example, when a bank makes a loan to a business it doesn’t give them banknotes, it simply credits their account with the size of the loan. Money is created in that instant. The new loan becomes an asset on the bank’s balance sheet, and the new deposits are a matching liability on the balance sheet (because they are owed to the customer). Viewed this way, bank deposits are simply a record of the amount of money a bank owes its customers.

Constraints

If a bank can just create money in this way, surely they’d do this infinitely? Luckily banks face a number of constraints:

- Risk mitigation and regulation: since loans are an asset of a bank, they must be fairly confident most of them will be repaid to keep their own business profitable. On top of that there is also a layer of regulation to make sure banks don’t hold too many risks (these could threaten the stability of the financial system)

An aside: a bank's business model is to lend out money (through loans, mortgages, credit cards) at a higher interest rate than they pay depositors for saving their money with the bank. The difference between these rates is what allows them to cover their costs and create profits.

-

Competitive forces: banks operate in a competitive environment so have to lend the money they create at competitive rates. To illustrate the example of competitive forces, let’s assume Bank A and Bank B are the only commercial banks in the economy. Bank A can lower rates to attract more customers to take out loans. However, if customers are taking loans from Bank A and using them to settle debts with Bank B, Bank A will have to use it’s reserves to pay Bank B (therefore Bank A will deplete its reserves and potentially expose itself to risk1). To avoid the customers taking money to other banks, Bank A can increase the rate of interest it pays on deposits to attract more customers to save with them. Therefore to be competitive it would have to lower the interest rate on new loans, and increase the interest rate on deposits. At some point this convergence will become unprofitable given there’s a cost to serve each customer.

-

Base interest rates: the ultimate lever on money creation is the central bank’s base rate. It influences the amount household and companies want to borrow. Banks receive interest on the reserves they place with the central bank. Whatever the base rate, they’ll charge their own customers a higher rate to borrow money. Otherwise it makes more sense for them to park their money in the central bank.

Destroying money

In the same way that money is created by banks. It can also be destroyed by consumers when they repay loans. For example, if you were to repay your mortgage in full you would immediately destroy the money that the bank created for that loan.

The above is a simplified explanation of how money is created in normal times. There’s obviously a lot of nuance involved, but I was surprised by some of things I learnt. It’s important to note that this is specific to the UK as the details vary by country.

1 In the UK banks don’t have to hold a minimum amount of reserves at the central bank. They just need to make sure they hold enough to clear their debts with other banks, or they’ll face very high rates on short term loans.